Like many of his generation of industrialists, Michael Crouch and his Zip Industries could have withered behind the tariff wall had it not been for his realisation that daring to be different was essential in order to survive and prosper.

That difference was his invention of an appliance to make instant boiling water, but he also applied constant innovation and marathon marketing to export it around the world. Today, millions of people in about 70 countries use Zip appliances, many of them made in its Bankstown factory in Sydney’s west.

Crouch, who passed away this month at the age of 84 after a battle with cancer, showed Australian business that innovation had to be matched with marketing to achieve global reach. In his twilight years, Crouch sold his majority share of Zip and emerged as an enthusiastic philanthropist and backer of causes including youth, the arts, and innovation development.

Raised in Sydney, Crouch attended the prestigious Cranbrook School but dropped out of university. With the support of his family, at age 28, he acquired a small hot-water company in Sydney called Zip Heaters. It had 12 employees and was one of dozens of similar companies competing in the domestic market.

Even though he applied innovation and committed marketing to his range of appliances – Zip’s heaters could be fitted directly above the kitchen sink or bath – he could see, by the late 1970s, that the writing was on the wall. It made him think about doing something different.

Invent to survive

“I tried to think of making something that no one else was making. I thought, ‘we’ve got to do something different to survive,’ ” he said in an interview to mark Zip’s 50th anniversary.

When he learnt a large block of units in Sydney was installing instant hot-water heaters, he thought about going a step further and conceived of the idea of instant boiling water.

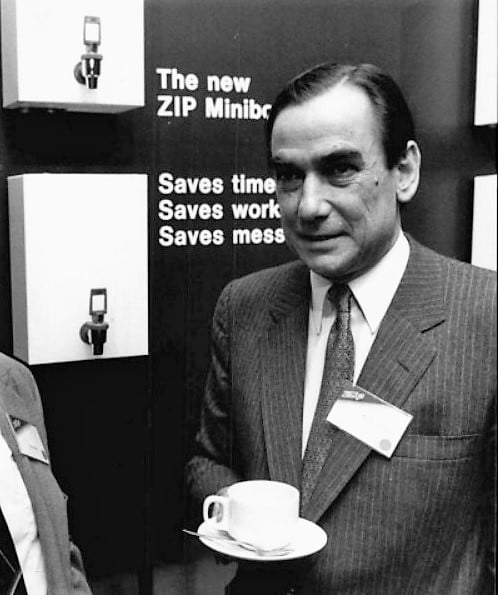

But a radical invention was no guarantee of success. He first developed a cumbersome unit that sold only a few hundred, so he refined it and made a neater appliance he called the “Miniboil”. This model – the familiar white box on the wall with the red tap – had instant appeal, and Crouch and his small marketing team hit the road to door-knock businesses and government procurement offices. They ran with the slogan “your tea rooms will no longer be waiting rooms”.

Not only was the product more convenient because staff weren’t waiting around for the jug to boil, Crouch’s design delivered boiling water more efficiently. Their first big contract was with the Commonwealth Bank, which like many big organisations at the time had employed “tea ladies”. The Miniboil made them redundant.

Within a decade, Crouch put a large picture of the Sydney skyline in his boardroom and marked each building that had Zip appliances with an orange dot. Nearly the entire skyline was covered in orange dots.

Going global

“We thought ‘if we can do that in Sydney, why can’t we do it in every city in the world?’” Crouch said.

Crouch said his export drive was helped by Australian trade officials who told him he should seek out local partners for distribution. His efforts in the UK, which included manufacturing, saw the appliances installed in Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, No.10 Downing Street, and both houses of parliament.

Close friend David Murray said Crouch realised that invention had to be matched by marketing.

“He didn’t believe that just because you have a patent or some proprietary know-how the world will give you anything. It is only as good as the marketing effort you put behind it,” Murray said. “What differentiated Michael Crouch from so many things produced here is that they run into difficulties with distribution networks around the world. He overcame that.”

Murray got to know Crouch when the two of them were appointed to APEC’s Business Advisory Council in the 1990s.

The Rich List

In more recent years, Zip targeted the domestic market with stylish, bench-top appliances that had the boiling system under the kitchen bench, and also supplied chilled and sparkling water. While the price tag for these units wasn’t cheap, they became sought after in the designer kitchen market.

After selling most of Zip to private equity in 2013, Crouch came up from under the radar and made his debut in the BRW Rich List. He sold his majority stake to private equity firm Quadrant, which last year on-sold to a US water treatment business for $550 million. This came after Quadrant abandoned plans for an IPO.

Crouch applied his wealth to a range of causes he cared about, including the Royal Flying Doctor Service and the Duke of Edinburgh award. He funded an expansion of Sydney’s historic Mitchell Library and a purpose-built innovation hub at the University of NSW, which opened in 2015. He developed a cattle business on properties near Scone and on King Island.

Perhaps more than anything, Crouch loved his country and was passionate about issues of national importance. His father had served in the Boer War and he was behind an initiative to have a monument built in Canberra, which is still a work in progress.

A prolific networker, he would host lunches at Sydney’s Union Club with guest speakers such as the former governor-general Michael Jeffrey in his capacity as federal government advocate for soil health. His annual Christmas lunch at the club included a who’s who line-up and many close friends.

Former prime minister John Howard, who knew Crouch well, described his business as a “manufacturing marvel” and Crouch as a “citizen in full’.

His contribution to Australian industry and philanthropy led to him being made a companion of the Order of Australia last year. He is survived by his wife Shanny, three children and six grandchildren.

Article by Paul Clearly Financial Review